The Tower of Babel: Biblical, Linguistic, and Archaeological Evidence

Biblical Evidence

According to the Book of Genesis, after Noah’s Flood all people spoke one language and settled in the land of Shinar (ancient Mesopotamia). There they began building a city and a great tower “with its top in the heavens” to make a name for themselves and avoid being scattered. Note that they also stated the purpose was so that they could be like God. The Genesis narrative states that God confounded their speech so they could no longer understand each other and scattered them across the earth, leaving the city called Babel unfinished. This brief account (Genesis 11:1–9) serves as an origin story explaining the diversity of languages in the world. Despite its brevity, biblical scholars note several concrete details in the text that suggest a memory of real Mesopotamian conditions and practices:

- Materials and Method: The builders use baked bricks and bitumen (tar) for mortar, as stone was scarce on the Mesopotamian plain. This matches the construction techniques of southern Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC, where kiln-fired bricks and asphalt were used for major structures due to lack of natural stone. The detailed description in Genesis 11:3 of making bricks and using bitumen is remarkably accurate to Mesopotamian technology, suggesting the story is grounded in that historical setting. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (1st century AD) also reiterated that the tower “was built of burnt brick, cemented with mortar made of bitumen”, underlining that this detail was long recognized in the tradition.

- Location – “Shinar”: Genesis locates this event in Shinar, which is broadly the region of Sumer and Akkad in southern Mesopotamia. The text also links the tower to the city of Babel, which is the Hebrew name for Babylon. In Genesis 10:10, Babel is listed alongside Erech (Uruk) and Akkad as early centers of Nimrod’s kingdom after the Flood. All these are real Mesopotamian cities, indicating the Bible places the Tower in the heart of Mesopotamian civilization. The builder is Nimrod, described as a mighty ruler and grandson of Noah’s son Ham. Later traditions identify Nimrod as leading the tower project in defiance of God. This casts the Babel episode as a direct rebellion against God’s command to “fill the earth,” consistent with the narrative context.

- Purpose and Pride: The biblical text emphasizes the builders’ pride and unity. They say, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves”. This hubris and desire for fame is portrayed as the reason God intervened. Many theologians take this as a cautionary tale against human arrogance. Theologian Augustine of Hippo (5th century) affirmed the historicity of Babel but interpreted it spiritually as human pride being humbled. The story’s theme (humanity trying to reach heaven, and God responding) parallels other biblical accounts like the fall of Adam or later the pride of Babylonian kings, reinforcing the moral lesson.

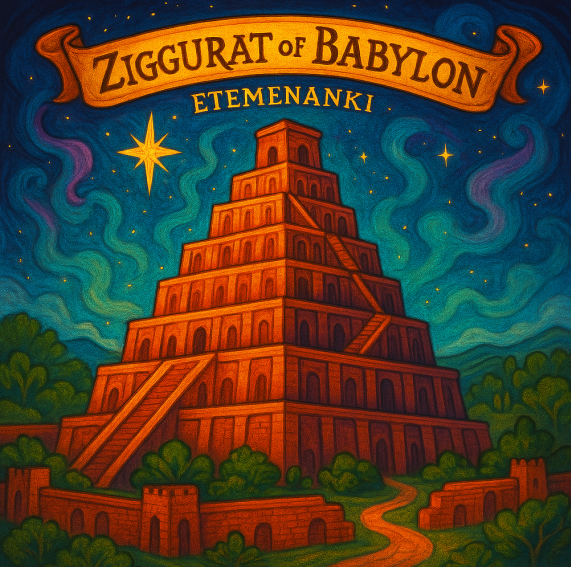

- “Top in the Heavens”: The builders aimed for the tower’s top to reach the sky. Notably, in ancient Mesopotamia the prominent temple-towers were ziggurats – massive stepped towers meant to connect earth and heaven. In fact, the famous ziggurat of Babylon was called Etemenanki, Sumerian for “Temple of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth”. Another ziggurat at Larsa bore the name “Temple that Links Heaven and Earth”. These names strongly echo the biblical phrase. This suggests the Tower of Babel story reflects an authentic Mesopotamian idea: building a man-made mountain to bridge the human and divine realms. The Hebrew word used for “tower” (migdal) in Genesis could refer to such a staged temple-tower. The detailed correspondence between the Genesis description and real ziggurats (location on a plain, baked brick construction, tar mortar, towering height, religious purpose to reach heaven) has been highlighted by scholars as evidence that the biblical writer knew of Mesopotamian tower buildings. It is unlikely a Hebrew writer living much later would accurately “invent” all these specifics without relying on genuine tradition or source.

Biblical literalists and many theologians thus believe the Tower of Babel was a real, historical construction. They see the Genesis account as preserved history from humanity’s early post-Flood era, when people still lived in one place. Early Jewish and Christian scholars treated it as factual: for example, Josephus recounts that Nimrod, “a bold man of great strength”, led people to build a tower so high “that it would be beyond the reach of any flood” in order to “avenge” their ancestors against God. He notes God frustrated this plan by multiplying languages, and that the place “now called Babylon” got its name from the confusion of tongues (the Hebrew balbel, to confuse, sounding like Babel). This same etymology is given in Genesis 11:9. In reality, Babylon’s name in Akkadian meant “Gate of God” (Bab-ili), but the Hebrew wordplay driving the story’s lesson – that human pride led to balbel (confusion) – is clear.

Other ancient sources outside the Bible also reference a great tower and a dispersion of languages, bolstering the idea that the Babel tale reflects a real history:

- The Babylonian priest Berossus (3rd century BC) wrote of an ancient giant tower in Babylon that was destroyed, and afterward the gods “introduced a diversity of tongues” among men. The Greco-Roman historian Abydenus, quoting Berossus, says the first men built “a tower that reached the sky” but it was overthrown by the gods and the people “received a confusion of tongues”. This is striking corroboration from a Mesopotamian source, preserving the same core elements (tower, divine destruction, confusion of language) as Genesis.

- Eupolemus, a Hellenistic Jewish historian (2nd century BC), likewise recorded that those who survived the Flood “built the tower… but when this was overthrown by the act of God, the builders were scattered over the whole earth”. He even notes these early builders were “giants” in his account, similar to other ancient legends.

- Later rabbinic and Islamic traditions also accept Babel as real. The Qur’ān alludes to people in Babylon taught by angels Harut and Marut (sometimes linked to Babel), and early Muslim historians like al-Tabari (9th century) recounted that Nimrod built a great tower at Babylon which God destroyed, creating 72 languages, leaving only one original language (in some Islamic tellings, the one preserved by Eber/Heber, the ancestor of Abraham). These later variants show the enduring influence of the story in Near Eastern thought.

In summary, traditional theological interpretation holds the Tower of Babel as an actual event in human early history. The convergence of the Genesis record with Mesopotamian building practices and other ancient accounts lends weight to this view. Table 1 below summarizes some key ancient sources about the tower and the confusion of languages beyond Genesis itself:

| Source (Date) | Account of the Tower of Babel (Key Details) |

| Hebrew Bible (Genesis 11) (c. 6th–5th cent. BC final form) | All humanity spoke one language; settled in Shinar and built a city and a tower “with its top in the heavens.” God confounded their speech and scattered them, and the city was called Babel (“because there the Lord confused the language”). |

| Flavius Josephus (Jewish historian, 1st cent. AD) | Describes Nimrod as leader of the Shinar project, urging mankind to build a tower high enough to withstand another flood. They built with burnt brick and bitumen mortar. God saw their wicked ambition, confused their languages, and scattered them. The ruins were called Babylon, meaning confusion. |

| Berossus (Babylonian priest, 3rd cent. BC), via Abydenus (c. 1st cent. BC) | Records that the first men, proud of their strength, built a huge tower in Babylon to reach heaven. The gods sent winds to topple the tower and mixed up the speech of the people, who until then spoke one language. |

| Eupolemus (Jewish Hellenistic writer, 2nd cent. BC) | Writes that after the Flood, people (giants) built the famous tower in Babylon. God overthrew the tower and scattered the builders “over the whole earth,” similar to Genesis. |

| Islamic tradition (e.g. al-Tabari, 9th cent. AD) | Nimrod (Namrūd) built a great tower in Babil. God destroyed it, and the one original language (often said to be Syriac or Hebrew) was split into 72 new languages. One righteous ancestor (e.g. Heber) was allowed to keep the original tongue. |

These accounts – Jewish, Christian, Babylonian, and Islamic – all treat the Tower of Babel as a real mega-project in Babylon’s early history that was divinely halted. They reinforce the core biblical claims: an ancient tower, suddenly halted and left incomplete, and a primordial time when humankind’s one language diverged into many. Such consistency across cultures and centuries is noteworthy. While modern scholars may label the story a “myth” or theological parable, it is clear that in the ancient Near East the Babel event was regarded as an authentic part of early human history.

Linguistic Studies and Language Diversification

One of the Tower of Babel story’s main implications is that the world’s many languages originated in a single sudden event. Theological perspectives that accept Babel as historical often incorporate this into models of language development. According to Genesis, prior to Babel “the whole earth had one language and a common speech”, often referred to as the Adamic or original language. After the tower builders’ language was confused, mankind was dispersed into different language groups (Genesis 11:7–9). This view implies a monogenesis of human language (a single origin) followed by a rapid polygenesis (splitting into multiple new languages).

In contrast, modern linguistic science finds evidence that languages evolve gradually over long periods, and most linguists consider the Babel account figurative. Historical linguistics holds that the diversification of languages is a slow, continuous process, not a one-time supernatural event. We do see a gradual changing of languages with time in thie history of mankind, but this does not override the narrative in Genesis simply by reason that when God changed the languages of men, their understanding of their new language was complete. They did however have the need to develop written forms of their writing, which is where we see the evolution of languages take shape. From the secular viewpoint, the Babel narrative is an etiological myth, and a literal reading that all languages suddenly appeared is at odds with a sudden appearance of languages. For example, by 3000 BC (the approximate timeframe some biblical chronologies might place Babel), there were well-established and mutually unintelligible languages in Mesopotamia (like Sumerian and Akkadian) and in Egypt (Egyptian language), which is distinctive support for the sudden change rather than the gradual development. We note when God confused the languages, he did a complete work. Historical evidence suggests that diversity existed instantaneously around the proposed date of Babel. Mainstream scholars, however, choose to ignore this and continue to regard the story as an ancient explanation for diversity, rather than a factual account of linguistic origins.

However, some researchers have explored whether all human languages could stem from a common source in prehistory (a concept known as the Proto-World hypothesis). The idea of a single original tongue for humanity was widely entertained in earlier eras: e.g. Medieval scholars believed Hebrew might be the primeval language spoken before Babel, calling it the language of Adam and Eden. During the Renaissance and up through the 17th century, many attempts were made to identify a living language that might be the direct descendant of the pre-Babel tongue (candidates ranged from Hebrew and Gaelic to Dutch and Swedish as nationalistic scholars each championed their own language). These attempts are now seen as misguided, but they show the lasting influence of the Babel narrative on linguistic thought up to modern times. The discipline of linguistics eventually moved away from trying to find an “Adamic language” as the evidence for any one surviving primeval language was lacking and the scientific study of language origins matured.

Today, most linguists think human language likely arose only once (monogenesis in the biological sense, since all humans share the capacity for language) but diversified slowly over tens of thousands of years as human groups spread out. The general consensus and narrative taught by linguists today is that language (in the sense of the first proto-language) probably originated with early modern humans in Africa or the Near East well over 50,000 years ago. By the time writing appears (c. 3200 BC), languages had already diverged into many distinct families. The Babel story compresses this process into a single moment and places it around the 3rd millennium BC. Linguists point out, for instance, that the Indo-European language family alone took millennia to branch out from a proto-language (Proto-Indo-European, spoken around 4000–3000 BC) into its descendants like Sanskrit, Greek, and English. Likewise, Afro-Asiatic languages (including Hebrew, Arabic, and ancient Egyptian) likely diverged from a common source possibly 8,000+ years ago, long before 2200 BC. So by the time of any proposed Babel incident, languages were already far more diverse than a single tongue. Note how modern scholars today slow down the time-frame of the narrative placing the languages outside of the biblical creation account, which also calls into question all of the Bible. This is a natural outcome of an evolutionary world view. This conflict leads scholars to label a literal reading of Babel “pseudolinguistics” when it comes to explaining language origins. Scholars choose to discredit the biblical account. We also note how the biblical text itself even hints at a more complex picture: Genesis 10 (the “Table of Nations”) lists Noah’s descendants “by their clans and languages”, seemingly implying multiple languages existed following Babel. We note how the text of Genesis was written after the Tower of Babel event. Note also how ancient commentators like Augustine suggest Genesis 11 actually “rewinds” to explain how those language families in chapter 10 came about.

From a faith-based perspective, researchers in creationist and evangelical circles have reconcile linguistic science with the Babel account. A common proposal is that Babel generated the root families of languages, which then diversified into the thousands of tongues we have today. Genesis 10 lists on the order of 70 ancestral family groups descending from Noah; these could correspond to ~70 original languages given at Babel. Notably, modern linguists classify languages into about 90 to 150 major families (depending on classification criteria). For example, all Indo-European languages form one family, all Semitic languages another, etc. The number of these families is on the same order of magnitude as the number of groups in the biblical account. Creationist linguists, such as those at the Institute for Creation Research (ICR) or Answers in Genesis (AiG), argue this is not a coincidence but evidence for Babel. They suggest that God’s confusion of tongues at Babel instantly created a set of distinct languages (perhaps dozens) which were the ancestors of each language family. Those initial languages would already have been fully-formed and complex (since humans were created with language ability from the start, in this view), allowing rapid development of dialects and daughter languages as people scattered.

There is some intriguing support for relatively rapid language divergence in scientific literature. Research published in Science (2008, Languages Evolve in Punctuational Bursts | Science) examined rates of vocabulary change and found evidence for an initial “burst” of changes when languages split off, followed by slower evolution over time. The study’s authors likened language splits to speciation events, noting that groups can quickly develop new linguistic quirks when isolated. Creationist commentators seized on this, saying it is consistent with an instantaneous Babel split followed by differentiation. They point out that when groups are isolated (geographically or socially), new languages can indeed form in just a few generations. For example, within recorded history we’ve seen new creole languages emerge from mixed populations, or dialects like American English diverging from British English in a couple of centuries. Mark Pagel, an evolutionary biologist, noted that when one community breaks off, identity and social factors can accelerate language changes. Creationist writers interpret this as exactly what would have happened after Babel: each group, now unable to understand others, would consolidate its own speech and rapidly develop further distinctions as they formed new communities. AiG concludes that “language families arose rapidly — instantaneously, in fact, at Babel,” and that from those families have come all the languages and dialects we see today. Subsequent gradual changes (sound shifts, grammatical drift, etc.) over the roughly 4,000 years since Babel would yield the 7,000+ languages currently spoken.

From the creationist perspective, several observations in linguistics and anthropology align with the Babel narrative:

- All languages equally complex: The world’s oldest written languages (Sumerian, Egyptian, Akkadian) appear fully developed with rich grammar and vocabulary from the start. There is no “primitive proto-language” known from evidence – the earliest records show language was already complex. This fits the idea that God created humans with language ability, rather than language evolving from grunts. (Linguists would argue complexity is not a simple linear evolution anyway, but this point is often raised in Babel discussions.)

- Rapid linguistic change: Languages can change so quickly that in a few centuries, dialects become mutually unintelligible. In just a few generations, a language can evolve or even go extinct. This shows how, after Babel, small migrating groups could develop very distinct tongues within a short time. Historical examples like Latin fragmenting into the Romance languages, or the hundreds of new languages formed in the colonial era (pidgins and creoles), illustrate fast diversification.

- Language families and distribution: Many of today’s languages trace back to a small number of ancient language families, suggesting a common source. For instance, about 7,000 living languages fit into roughly 136 families, and 80% of the world’s population speaks a language from just a dozen of these families. This “clustering” is seen as consistent with a few original languages at Babel fanning out. If 70–100 new languages were supernaturally created at Babel, it is plausible that some died out or merged over time, while others expanded. The dominance of a few families (like Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Niger-Congo, etc.) could reflect the success and spread of certain Babel groups.

- Genetic and linguistic correlations: Studies in genetics have often noted that genetic diversity patterns in populations correlate to some extent with language families and migration patterns. One observation cited is that DNA analysis shows humanity’s diversification is consistent with a single dispersal (out of Africa, in mainstream science) and subsequent rapid branching – which creationists equate to the post-Babel dispersion. While mainstream scientists interpret these data in evolutionary terms, some see it as supportive of the idea that as people scattered from a point of origin (Mesopotamia/Shinar), they carried their new languages with them, and certain linguistic and genetic groupings overlap.

- Global “confusion” legends: Remarkably, many cultures have ancient legends about a time when everyone spoke the same language and then the tongues were divided. Anthropologists in the 19th–20th centuries (like James Frazer) documented stories from places as far as India, Africa, and the Americas describing a fall of mankind’s original unity of speech. For example, the Kʼicheʼ Maya in Guatemala told of gods who vexed the language of people so they could not understand each other, and a Polynesian myth from the Maori speaks of an ancestral deity who upset mankind’s unity of speech. The Greek myth of the giant Aloadae or of Hermes confusing languages is another echo. None of these involve a tower, but the motif of divine confusion of language is present. The widespread distribution of such tales could be interpreted (from a biblical perspective) as independent cultural memories of the Babel event, just as flood myths around the world are seen as reflecting a real Flood. Even the Americas, far removed from the Near East, had tribes like the Maidu and Tarahumara with myths of a single language in the distant past that was split by the gods. This anthropological data, while not “proof,” intriguingly aligns with Genesis and is often cited by those arguing Babel was real.

On the other hand, secular linguists caution that language diversification clearly predates any plausible date for Babel. For instance, the Sino-Tibetan family (which includes Chinese and Tibetan languages) likely began diverging by 4000–3000 BC or earlier, and Austronesian languages started spreading from Taiwan around 3000 BC. Many of the indigenous languages of the Americas and Africa have been separate for far longer. We note that from the Tower of Babel timeframe, all of these Chinese and Tibetan tribes needed to migrate to their respective locations, and they went with fully developed language sets based upon God having done this intentionally to disperse the people. So when the people arrived at their location and began constructing buildings with their language inscriptions, it would appear as if these languages already existed. We also note how languages share deep connections – for example, Indo-European and Afro-Asiatic likely had no recent common origin, but both may ultimately trace back to the very early human language(s

In summary, theological and creationist studies on language maintain that the Tower of Babel was the pivotal event that triggered the diversification of tongues. They correlate the approximately 70 families from Babel to the ~100+ known language families, and point to the feasibility of rapid language formation. They also highlight that the earliest civilizations all appear suddenly with fully formed languages near the Middle East (Sumerian, Egyptian, etc., emerging around the same time), which they argue is best explained by a recent creation of languages rather than a long evolution. Mainstream linguistic research, however, supports that languages evolved from earlier ones gradually, with no need for a miraculous trigger in the Bronze Age. Still, the notion of an original single language is not entirely dismissed by linguists – many consider it possible that all human languages ultimately go back to one proto-human tongue. The debate between these perspectives continues in faith circles, but it’s clear that the Tower of Babel story has prompted serious consideration of how languages spread and diverged in human history.

Archaeological Evidence

Because the Tower of Babel narrative is set in a real geographic location (Babylon in Mesopotamia), archaeologists and historians have naturally looked for evidence of such a structure or event. While no direct artifact labeled “Tower of Babel” has been found, there is significant archaeological evidence of ancient Mesopotamian towers that matches the Bible’s description. Some findings are widely accepted (like the known ruins of large ziggurats in Babylon), and others are more speculative (attempts to link specific archaeological remains to the Babel event). Here we review the key evidence:

1. The Ziggurat of Babylon (Etemenanki): It is commonly believed by scholars that the biblical Tower of Babel corresponds to the great ziggurat of Babylon, known as Etemenanki. Etemenanki was a massive stepped tower dedicated to the god Marduk, located in the city of Babylon (today in Iraq). Archaeologically, its remains were excavated in the early 20th century. German archaeologist Robert Koldewey uncovered the huge square platform and foundations of this ziggurat around 1913. Though much is ruined, its base was about 91 meters (300 feet) per side, and it probably stood 70–90 meters tall originally (seven or eight staged levels). Cuneiform texts from Babylon describe the tower in detail: a Babylonian inscription of King Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC) on a stele – sometimes called the “Tower of Babel Stele” – records his refurbishment of this structure. Notably, Nebuchadnezzar boasts: “Etemenanki, Ziggurat of Babylon, I made it, the wonder of the people… I raised its top to heaven, made doors for the gates, and I covered it with bitumen and bricks.”. This inscription (now in the Schøyen Collection) explicitly parallels the wording of Genesis: “its top to heaven” and the use of baked brick and asphalt. It demonstrates that a monumental tower did exist at Babylon, constructed with the exact materials and ambition described in the Bible. Another inscription, on foundation cylinders of Nebuchadnezzar’s father Nabopolassar (c. 610 BC), says Marduk commanded him to rebuild Babylon’s ziggurat and to make its “top vie with the heavens”. These finds confirm that the Babylonians themselves saw their ziggurat as a colossal tower reaching the sky.

Furthermore, archaeologists have found a formal building inscription tablet that gives the dimensions and materials of Etemenanki, essentially a “tower blueprint.” It mentions the use of asphalt (bitumen) and baked brick throughout – precisely the combo noted in Genesis 11:3. The ruins at Babylon correspond to this: excavations uncovered thick layers of bitumen and brick, and remnants of the tower’s base. The building was originally started much earlier (possibly in the second millennium BC or before – some historians suggest it was first built by Hammurabi or even earlier). Over centuries it was destroyed and rebuilt multiple times. By the Neo-Babylonian period (626–539 BC), Etemenanki was of such legendary status that Greek historians wrote about it. Herodotus (5th century BC) gave an account of a “Temple of Belus” in Babylon, describing a gigantic tower with eight levels and a temple at the top, accessed by a spiral ramp. Although some of Herodotus’s description is exaggerated or confused, it aligns with a multi-tiered ziggurat structure.

Importantly, the city of Babylon was destroyed in 689 BC by the Assyrian king Sennacherib, who claimed to have razed the ziggurat. It was later rebuilt by Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II, then ultimately fell into ruin after Babylon’s conquest by the Persians and later neglect under Alexander the Great (who attempted repairs). By the 1st century BC, only a mound remained. So, by the time Genesis was compiled, the tower’s ruins were likely visible (and perhaps being reinterpreted through story). The discovered inscriptions from Babylon leave little doubt that a real soaring tower stood there in antiquity, fitting the general parameters of the biblical Tower.

2. The Borsippa Tower (Birs Nimrud): About 11 miles southwest of Babylon lie the ruins of another ancient ziggurat at Borsippa. The site is known today as Birs Nimrud (“Tower of Nimrod”) because local folklore connected it to Nimrod’s tower. This ziggurat was dedicated to the god Nabu and was also massively built, though not as large as Babylon’s. Excavations and inscriptions revealed something intriguing: Nebuchadnezzar II also worked on this tower. Clay cylinders found in the ruins (the “Borsippa Cylinders”) contain Nebuchadnezzar’s inscription where he calls the structure the “Tower of Babylon” and the “Tower of Borsippa” interchangeably. He states that a “former king built it but did not complete its head,” and that over time it had crumbled. Nebuchadnezzar claims he resumed work to finish its summit, without altering the original foundation. This is remarkable because it implies an ancient unfinished tower that was left standing incomplete. Even more, the name Borsippa in the local language was interpreted as “Tongue-Tower” or “Tower of Tongues”. Nebuchadnezzar’s text uses a pun: calling Borsippa “the Tongue-Tower” which certainly invites a connection to the confusion of tongues at Babel. Scholars have noted that Borsippa’s ziggurat might have been associated in Babylonian tradition with a tale of an incomplete tower and possibly a language-dividing event (though no direct Babylonian text says the gods confused tongues there, the name is suggestive). The Borsippa ruin still stands about 52 meters high today – a jagged crumbling mass of brick that indeed looks “half-finished.”.

Ruins of the massive ziggurat at Borsippa (modern Birs Nimrud in Iraq), often linked to the Tower of Babel. Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt this tower in the 6th century BC, noting that a former king had left it unfinished, “not completing its head”. The site’s ancient name Borsippa means “Tongue Tower,” hinting at the confusion-of-language legend.

Some historians propose that later generations conflated the Borsippa tower with the legend of Babel, especially since Babylon’s own ziggurat was fully rebuilt by Nebuchadnezzar but Borsippa’s remained partially in ruins. The name “Tongue Tower” is hard to ignore – it provides a potential direct link to the Babel story. In any case, both Babylon’s and Borsippa’s ziggurats demonstrate that the region had multiple enormous towers. Nebuchadnezzar’s records show an awareness of antiquity: he refers to an ancient (possibly pre-Babylonian) attempt to build a tower that was not finished. This raises the tantalizing idea that Nebuchadnezzar himself had heard a tradition of an age-old unfinished tower – perhaps the very tradition the Genesis story is based on.

3. Ancient Mesopotamian Tablets (Cuneiform Texts): Beyond physical ruins, archaeologists have uncovered cuneiform tablets that appear to preserve Mesopotamian versions of the Babel tale. One tablet, found in the 19th century in the ruins of Nineveh (northern Mesopotamia, in the library of Ashurbanipal), now in the British Museum, contains a fragmentary story often called “The Babel Episode.” In this Assyrian text, the gods (or a god) destroy a building—specifically in Babylon—and “confuse the speech” of the builders. The tablet is broken, but words for ruin and mixing languages are clearly discernible, paralleling the biblical account. The Assyrian scribe actually uses the phrase for “mixed tongues” that corresponds to the Hebrew balbel (to confuse) used in Genesis. This shows the story of divine confusion of language was known in Mesopotamia. Another source, a tablet in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford), contains an ancient Sumerian or bilingual text which describes a time when “all people spoke one tongue” and then the god “Enki (lord of Eridu) confused their speech”. One line says: “In those days…the people… could address Enlil in but one tongue. … (Then) the lord of Eridu estranged their tongues in their mouths.”. Eridu is an extremely old city in Sumer; notably, some later Babylonian writers equated Eridu with the site of the Babel tower (one tradition even calls the place of the tower Eridu). This tablet suggests a Sumerian precursor to the Babel story, where a god’s act causes human language to become “estranged.” The fact that this tablet was found and translated by modern scholars powerfully confirms that the elements of the Babel saga (one language, divine confusion, scattering) were part of Mesopotamian lore independent of the Bible. It likely dates to at least the 2nd millennium BC. These archaeological finds of text provide independent witness that the story was not an invention of Israelite authors—it was circulating in Mesopotamia in various forms.

4. Eridu’s Unfinished Tower: Eridu, mentioned above, is often cited by some archaeologists and biblical researchers as a compelling site in connection with Babel. Eridu (modern Tell Abu Shahrain in Iraq) was one of the earliest cities in Mesopotamia (dating back to 5400 BC) and revered by the Sumerians as the first city established by the gods. At Eridu, excavations have uncovered a large step/platform temple structure in its final layer (dated roughly to the late 4th or early 3rd millennium BC) that appears left unfinished. Archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley noted that at Eridu the construction of a gigantic ziggurat-like platform was abruptly halted in antiquity and never resumed, with bricklayers’ tools left at the site – suggesting a sudden interruption. Some have speculated this could be the remains of the very tower of Babel. While this is not a mainstream view, it’s intriguing: Eridu was abandoned for a time and a wave of cultural dispersal known as the Uruk Expansion followed soon after (around 3500–3000 BC, Uruk culture spread north and east). Those who favor this theory argue that Eridu fits the description of Babel as “the world’s first city” in post-Flood times. The name “Babylon” might have later been applied to that event, or the stories merged. It’s speculative but worth noting that there is archaeological evidence of a halted building project in the right region and era. To date, however, Babylon’s own ziggurat is a more concrete candidate for the Tower of Babel, and it’s possible the Genesis account conflated memories of multiple towers (Eridu, Borsippa, Babylon) into one grand narrative.

5. Global Cultural Evidence – Pyramids and Towers Worldwide: Although not “evidence” in the direct sense, many writers have pointed out the curious fact that ancient cultures across the world built pyramid-like structures, suggesting some shared inspiration. Mesopotamia had ziggurats; Egypt, pyramids; Mesoamerica, pyramid-temples; India and Southeast Asia, stepped temples; China, pyramidal mounds – all with analogous form. These structures are often cultic or cosmological symbols (holy mountains). It is remarkable that even peoples with no known contact ended up constructing massive pyramids of similar design. Those who take the Babel account literally propose a compelling explanation: the builders of Babel carried the concept of the tower with them as they scattered. In other words, the knowledge of how to build large brick pyramidal structures and the religious notion of reaching heaven or contacting gods on high was dispersed from a single source (Babel). This could explain why, for example, the Maya built towering step-pyramids in the remote Yucatan, or why pyramid structures arose in distant corners of the earth in the third millennium BC. Secular historians usually attribute this to parallel development (since a pyramid is a logically stable way to build high with primitive technology). Yet the similarities are striking enough that even some evolutionist researchers are puzzled by the rapid rise of advanced construction know-how in separated societies. A shared origin via Babel would neatly account for it. While circumstantial, the global pyramid phenomenon aligns with the idea of a dispersion from Mesopotamia of people who had a common technological and religious heritage.

The table below summarizes key archaeological findings and how they relate to the Tower of Babel narrative:

| Archaeological Find or Source | Description and Relevance to Babel |

| Babylon’s Great Ziggurat (Etemenanki) – Ruins and Inscriptions | Ruined massive brick tower in Babylon (90m base). Inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II describe rebuilding it: “I raised its top to heaven… coated it with bitumen and bricks.” Matches Genesis: tower with “top in heavens,” bricks and tar. Widely seen as the inspiration for the biblical Tower of Babel. Herodotus also described this multi-tiered tower. |

| Borsippa Ziggurat (Birs Nimrud) – Unfinished Tower and Cylinder Inscriptions | Remains of a large ziggurat at Borsippa, long called “Nimrod’s Tower.” Nebuchadnezzar’s cylinder says a former king built it to 42 cubits high but “did not finish its head.” Nebuchadnezzar repaired it but called it the “Tongue-Tower” (Tower of Borsippa). Suggests an ancient, aborted tower-building project and links to “tongues” (languages) legend. |

| Assyrian Tablet from Nineveh (c. 7th cent. BC) – “Babylon Tower” fragment | Fragmentary clay tablet (British Museum) recounts a deity destroying a structure (in Babylon) and confusing the speech of the builders. Uses wording analogous to Genesis (“mixed their words”). Shows Mesopotamians had a tale of a thwarted tower and language confusion, independent of the Bible. |

| Sumerian Tablet (Ashmolean Museum) – One Tongue to Many | Ancient tablet text citing that once “the whole universe” spoke in one tongue, then the god of Eridu “estranged their tongues”, making the languages many. Explicit ancient record of language diversification by divine act. Locates event at Eridu (S. Mesopotamia). Corroborates the concept of Babel in local myth. |

| Eridu Ziggurat Ruin (Tell Abu Shahrain) – Abandoned Construction | Archaeological site of Eridu has a massive ziggurat foundation from the late 4th millennium BC that was started and left incomplete. Brick construction abruptly halted (tools left behind). Some suggest this could be the actual Tower of Babel remains (speculative, but Eridu was known as the first city). |

| “Tower of Babel Stele” (Schøyen Collection, c. 6th cent. BC) – depiction of the Tower | A carved stone stele believed to show King Nebuchadnezzar II alongside a large ziggurat (with a schematic illustration of its stages). The inscription labels the tower and describes its grandeur. Visually confirms the ziggurat’s appearance and the king’s role. Often used to illustrate the real tower that inspired the Babel story. |

| Global Pyramid Structures (Egypt, Americas, etc.) – Cultural Echoes | Dozens of ancient civilizations built pyramid/ziggurat structures by 2000–1000 BC. They share architectural and religious features despite no direct contact. One hypothesis is that the idea and skills spread from a single point (Babel) as people migrated. This would make the Tower of Babel the “mother” of later pyramids conceptually. |

As seen above, the hard evidence confirms that ancient Mesopotamians were tower-builders and that myths of a thwarted tower and confused speech were part of their culture. The Babylonian ziggurat was real and awe-inspiring – its ruins match the biblical account in materials and scale. Archaeologist Dr. George A. Barton once wrote, “The ziggurat of Babylon undoubtedly gave rise to the story of the Tower of Babel”. Even the secular perspective concedes that Genesis reflects a folk memory of real towers, especially the one in Babylon. There is no known archaeological artifact explicitly labeled as “Noah’s Babel Tower,” but the convergence of Babylonian records, Mesopotamian legends, and physical ruins provides a compelling case that the story has a historical core.

It’s also worth noting the historical timing: Many believe the Babel incident, if historical, occurred in the 3rd millennium BC (somewhere between 3000–2000 BC, after the Flood and before Abraham’s time). Mesopotamia at that time saw the rise of the first cities (Uruk, Eridu, Babel) and the construction of the earliest ziggurats. Indeed, the Uruk period (c. 4000–3100 BC) and Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2350 BC) saw explosive urban growth and monumental architecture in Sumer. This is exactly when and where we’d expect the Tower of Babel. The archaeological record shows that languages like Sumerian and Akkadian coexisted in Mesopotamia by 2500 BC, which could correspond to the post-Babel linguistic diversity. And the large-scale migration of people and culture outward (the Uruk Expansion) fits with a dispersal from a central region. While traditional biblical chronology (e.g. Archbishop Ussher’s dating) places Babel around 2242 BC, even those who don’t hold to such precise dating see that something significant happened in human prehistory: sudden civilization dispersal and sudden linguistic diversification – which is exactly what Genesis reports.

In conclusion, archaeology does not contradict the Tower of Babel story; it broadly supports it. We have physical remains of gigantic Mesopotamian towers and written testimonies from antiquity that mirror the Bible’s claims. The identification of Babylon’s ziggurat with Babel is widely accepted in scholarly circles. The additional evidence of the Borsippa “Tongue-Tower” and the ancient tablets about one tongue further strengthen the case. Even if one views the Babel narrative as symbolic, it is clearly rooted in real places and practices of Mesopotamian history.

Historical Context of Mesopotamia and Babel

The Tower of Babel story is deeply embedded in the historical context of ancient Mesopotamia, often called the “Cradle of Civilization.” Understanding the setting of Shinar/Babylonia in the early post-Flood era (as the Bible frames it) or in the dawn of recorded history (as secular history frames it) is key to appreciating the narrative’s background and significance.

Mesopotamia – Land of the First Cities: Mesopotamia (the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, modern Iraq and eastern Syria) was home to humanity’s first large urban centers. After a long period of human migration and small villages, suddenly around 3500–3000 BC cities like Uruk, Eridu, Ur, Kish, Akkad, and Babylon emerged with advanced organization. This correlates remarkably with Genesis 10–11, which describes the descendants of Noah settling in Shinar and building the first city (Babel) and others. In fact, Genesis 10:10 names “Babel, Erech, Akkad” as the beginning of Nimrod’s kingdom. Erech is the biblical name for Uruk, which historians recognize as the world’s oldest city (Uruk in Sumer was flourishing by 3200 BC). Akkad was the capital of Sargon of Akkad’s empire (c. 2300 BC) and has legendary status (though its site remains archaeologically unidentified, its existence is certain). The mention of these real cities in Genesis shows the biblical authors knew that the earliest civilization was in Mesopotamia. Nimrod, described as a “mighty hunter” and potentate, likely symbolizes those first empire builders (some link Nimrod with Sargon of Akkad or with the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta or other figures, though no consensus). In any case, Mesopotamia is the theater of action for the Babel episode, implying that the Hebrews remembered civilization starting there, not in their own land. This aligns with archaeological fact: Mesopotamia and Egypt are where writing, urbanism, and monumental architecture began.

Ziggurats and Mesopotamian Religion: A critical piece of context is the role of ziggurats in Mesopotamian culture. Ziggurats were essentially man-made holy mountains – massive brick towers with temples on top – built in the heart of cities to honor the patron god. They believed gods dwelt in the high heavens but could come down to the mountaintop shrine. The names of ziggurats (like Etemenanki, “Foundation of Heaven and Earth”) reveal their purpose: to connect heaven and earth. The Bible explicitly says the Babel tower was built to reach the heavens, which is exactly what ziggurats were meant to do. In Mesopotamian belief, each city had a patron deity with a temple atop a ziggurat, and rituals would involve ascending these towers. The famous image of a stairway to heaven (like the one Jacob saw in his dream in Genesis 28) could well be inspired by a ziggurat’s stairway. So the Tower of Babel can be seen as a human attempt to access divine space, typical of Mesopotamian religion. However, the Genesis spin is that this attempt was done in pride and without God’s sanction, thus God confounded it.

In the ancient Near East, building projects (especially temple towers) were often done with great ceremony, sometimes involving the whole community or forced labor from many nations in an empire. For example, texts record that when Nebuchadnezzar rebuilt Etemenanki, he mobilized people from conquered lands to work on it (hence his boast that it was “the wonder of the people of the world”). This is interesting considering Genesis says originally “the whole world had one language” and cooperated in building the tower. It might reflect a memory of a time of united human effort in such a project.

Political Power and “Name-making”: Genesis 11:4 has the people say, “Let us make a name for ourselves.” In Mesopotamian context, building a spectacular city and ziggurat was indeed a way for a king and people to make a name (reputation). Kings inscribed their names on bricks (thousands of Nebuchadnezzar’s bricks stamped with his name have been found at Babylon) and steles to immortalize their achievements. The lure of fame and glory drove much of Mesopotamian statecraft. Nimrod, as a mighty king, exemplifies this ambition. Thus, the Babel story also critiques the early tyrants who tried to aggrandize themselves (Nimrod in legend). Interestingly, Babylon in later biblical tradition becomes synonymous with arrogance and defiance of God – “Babylon, the great” in Revelation, or the hubris of Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel. The Babel narrative can be seen as the origin of that spirit: the first Babylon (Babel) set the pattern of imperial pride that God ultimately humbles. Historically, Babylon was a powerful city-state by the 18th century BC under Hammurabi, and later the capital of an empire under Nebuchadnezzar (6th century BC). But in much earlier times (3rd millennium), it was likely a smaller city overshadowed by older ones like Uruk and Akkad – which is precisely when the Bible suggests “Babylon/Babel” first rose to prominence (under Nimrod). Some historians propose the possibility that the tower myth arose to explain why people speak different languages despite living relatively close – for example, the Sumerians and Akkadians lived in the same region but spoke unrelated tongues. The ancient Sumerians might have wondered, “why do our neighbors speak a different language if we all came from common ancestors?” A story of a divine act could serve as an etiology.

Mesopotamian Language Diversity: Mesopotamia itself was linguistically diverse very early. By 2500 BC, Sumerian (a language isolate) and Akkadian (a Semitic language) were both widely used, requiring bilingual scribes. Later came Aramaic, Hurrian, Elamite, etc., in the region. So, Mesopotamia was likely the first place on earth where multilingual interaction was a known fact. It’s conceivable that the Babel story was influenced by awareness of an earlier time when perhaps only one of those languages was spoken, and the subsequent emergence of others. Sumerian texts like “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta” actually yearn for a return to a unified language so all peoples can praise the god Enlil together – implying a cultural memory (or ideal) of unity lost. That epic references Enki confusing the tongues of presumptuous rulers, which is clearly parallel. The historical interaction of different language groups in Mesopotamia likely informed such stories. The Table of Nations in Genesis 10 divides humanity into family-nations descending from Shem, Ham, Japheth, each with their own languages, and attributes many of those lineages to known ethnic groups (for example, descendants of Shem include Akkadians, Arameans, Hebrews; descendants of Ham include Egyptians, Canaanites, possibly Sumerians). So the Hebrews were attempting to sketch out how the world’s peoples and tongues came to be, with Mesopotamia as the starting point. This reflects an ancient understanding that civilization radiated outward from Mesopotamia – which archaeology confirms (e.g. influence of Mesopotamian culture on the Levant, Egypt, Anatolia in early Bronze Age).

Historical Memory in Exile: Another relevant context for the writing down of the Babel story is the Babylonian Exile of the Jews in the 6th century BC. Modern scholarship often suggests that the form of Genesis we have was compiled or edited during the Exile (after 586 BC), when the elite of Judah lived in Babylon. These exiles would have seen firsthand the imposing ziggurats of Babylon and Borsippa (some ruins still stood, or even partially intact in Nebuchadnezzar’s time). Imagine Jewish scribes walking by the towering Etemenanki or the crumbled “Tongue-Tower” of Borsippa and recalling the old tale of human pride and divine judgment! It’s very plausible that they identified those structures with the ancient Tower of Babel and incorporated local Babylonian lore. One clue is that the name Babel is treated as if from Hebrew balbel (confuse), a play on words that a Babylonian local might have mentioned (Babylonians themselves would not derive it that way, but exiled Judeans punning in Hebrew would). Scholars argue that Genesis 1–11 contains several Babylonian cultural echoes (e.g. the Flood story parallels the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh). Encyclopædia Britannica notes that the Babel story likely was influenced by seeing the ziggurat of Babylon and hearing local traditions about it. One historian writes that exiled Judeans, humbled by Babylon’s might, turned the tower – a symbol of Babylonian arrogance – into a cautionary tale that even the greatest city’s pretensions can be brought low by God. Thus, historically, the Babel story may serve as a coded critique of Babylon: at a time when Babylon had destroyed Jerusalem, the Jews told a story of how long ago Babylon itself was thwarted by God and scattered. This adds a layer of meaning: it’s not just about ancient history, but about the recurring conflict between human empire and divine will.

Mesopotamia as a Center of Dispersion: Mesopotamian history shows many dispersions of people. For instance, after the collapse of the Sumerian civilization (around 2000 BC), people migrated and new nations arose (Amorites in Mesopotamia, Hurrians to the north, etc.). The “scattering” in Genesis might reflect memory of a real migration wave. As mentioned, archaeologists identify an expansion of southern Mesopotamian culture during the Uruk period, where colonies of Mesopotamian traders and artisans popped up in Turkey, Syria, Iran. It’s almost as if people from the Mesopotamian plain suddenly spread out – which could be seen as evidence of the Babel dispersal. Later, the fall of the Akkadian Empire (~2200 BC) led to movements of peoples (Gutians, etc.). While Genesis condenses everything into one event, in reality there may have been a series of dispersals. Mesopotamia’s central location meant that as population grew, groups fissioned off and migrated outward to found new civilizations – in the Levant, Egypt, the Indus Valley, Central Asia, etc. All these new civilizations that sprang up in the early Bronze Age could trace a cultural lineage back to Mesopotamia. It is striking that Sumerian influence is detected as far as the Nile and the Indus by 2500 BC (e.g. similar architectural forms, artifacts). This suits the idea that after Babel, “from there the Lord scattered them over the face of all the earth”. Mesopotamia was indeed the fountainhead from which technology, ideas, and people spread in all directions.

Legacy of Babel in Mesopotamia: Mesopotamian literature after the Babel timeframe continued to recall an ideal time of unity. The epic poem “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta” (circa 2100 BC) has a passage praying for a future restoration of a single language among all peoples. It references that initially Subur, Hamazi, Sumer, Akkad – all the lands – spoke to Enlil in one tongue, but then something changed (implying multiplicity of tongues), and it looks forward to a day all will speak one language again. This indicates the Mesopotamians were conscious of linguistic disunity as a post facto situation and perhaps wistful about a lost unity. The Bible of course portrays that unity as broken by God due to human pride, whereas Enmerkar’s story portrays the confusion as a strategy by a god to end human “ambition” for a unified culture that might challenge the gods. Both perspectives actually dovetail whether it’s God’s punishment or a preventative measure by the gods, the result is the same – no more single language. It’s fascinating that both traditions exist side by side in the same region’s lore.

Mesopotamian Aetiology: The Babel story also fits into a broader Mesopotamian pattern of explaining origins. Mesopotamian myths often explain why things are the way they are (why we die, why we have summer and winter, etc.). A Sumerian myth tells of how the gods, once united, got into quarrels resulting in various outcomes. The idea that the world’s diversity of languages needed an explanation suggests that early people were indeed puzzled by diversity. In a time when nations encountered each other (through trade or war), the question “why don’t we all speak the same language if we all came from the gods or from one family?” naturally arises. The Babel tale provided an answer anchored in the moral of human limitation: there are boundaries humanity cannot cross without divine permission (such as reaching heaven on their own or concentrating too much power). Historically, in Mesopotamia, when emperors overreached, often their empires fragmented – a parallel to Babel’s outcome. The Akkadian Empire of Sargon, for instance, united many peoples under one rule (one could analogize to one “speech” i.e. one administrative language, Akkadian) but collapsed into chaos after a couple of centuries. Similarly, Babylon under Nebuchadnezzar united many nations (using Aramaic as a lingua franca), but after his death it quickly fell apart and eventually foreign languages (Persian, Greek) took over. Thus, one can see in the sweep of Mesopotamian history a recurring “confounding” of unity. The Babel story in Genesis might be read as a paradigm: whenever humans arrogantly seek total unity and self-sufficiency (especially in a city like Babylon), God intervenes to scatter and humble them – a theme resonant to the exiled Jews who saw Babylon fall to Cyrus of Persia, ending their exile.

In summary, ancient Mesopotamia provides the perfect real-world canvas for the Tower of Babel narrative. It was a land of innovations (brick technology, city-building), grand construction (ziggurats that inspired the idea of reaching heaven), and emerging linguistic diversity. The early post-Flood generation in the Bible corresponds to the Ubaid/Uruk era when people congregated and then, seemingly suddenly, dispersed. Mesopotamia’s history of building projects and multi-ethnic empires fits the motifs of the story. And the later Hebrew writers, living under Babylonian dominance, would have had every historical and visual incentive to memorialize the lesson that “Babylon’s power and hubris are nothing before God.” Babel, literally Babylon, stands as a symbol of human civilization – capable of great achievements (a unified culture, a mighty city, towering architecture) but always under the sovereignty of the Creator, who can check human pride in an instant.

Ultimately, whether taken as literal history or as a theological saga grounded in historical memories, the Tower of Babel is inexorably linked to Mesopotamia’s legacy: it is the Bible’s explanation for how the world’s myriad cultures and languages sprang from one source in the Fertile Crescent. Archaeology and historical study continue to shed light on that very question, often affirming elements of the biblical account even as they provide naturalistic explanations. The enduring image of a doomed skyward tower remains a powerful warning from humanity’s earliest chapters. The bricks of Babel, baked in the Mesopotamian sun, still speak to us from the dust of Iraq, telling a story of human ambition and divine ordinance that has echoed through cultures for millennia.

Bibliography

Biblical and Historical Sources

- Genesis 11:1–9 — The Tower of Babel account

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book I, Ch. 4

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/josephus/ant-1.html - Augustine, City of God, Book XVI, Ch. 11

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/120116.htm - Berossus, fragments preserved by Abydenus (quoted in Eusebius)

Referenced via W.G. Lambert’s work (see academic compilation below)

Linguistic and Theological Studies

- Duursma, K. J.

Language at Babel: Divine Origin or Evolution?

Creation Ministries International, 2001.

Available at: Creation.com article - Atkinson, Q. D., Meade, A., Venditti, C., Greenhill, S. J., & Pagel, M.

Languages Evolve in Punctuational Bursts.

Science, Vol. 319, Issue 5863, pp. 588, February 1, 2008.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1149683 - Hayes, Bruce.

Phonological Typology and Historical Linguistics.

In Introductory Phonology, Chapter 3. UCLA Linguistics Course Materials.

PDF available at: UCLA Linguistics - Answers in Genesis: “Tower of Babel—Origin of Nations and Languages”

https://answersingenesis.org/tower-of-babel/

Archaeological Evidence and Tower Candidates

- George, Andrew, ed. Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection. Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology, Vol. 17. CDL Press, 2011. This includes the stele as Text 76, pp. 153–169, with plates LVIII–LXVII.

- Koldewey, Robert.The Excavations at Babylon. Translated by Agnes S. Johns. London: Macmillan, 1914. Available via Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive. This is the definitive English edition of Koldewey’s findings, including architectural plans and stratigraphic notes from the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft’s work between 1899–1917.

- Oppert, Julius. Expédition Scientifique en Mésopotamie exécutée par ordre du gouvernement de 1851 à 1854, Vol. I. Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1863. This volume includes Oppert’s French translations and commentary on inscriptions from Borsippa, including the cylinder texts. You can access a digitized version via Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France) — search within for “Borsippa” or “Nebuchadnetsar” to locate the relevant sections.

- Supporting Artifact Record: The actual cylinder (British Museum Object No. K.1685) is cataloged in the British Museum’s collection, with bibliographic references to Oppert’s work in Journal Asiatique (1857) and Grundzüge der Assyrischen Kunst (1872).

- nmerkar and the Lord of Aratta: A Sumerian Epic Tale of Iraq and Iran Author: Samuel Noah Kramer Publisher: Wipf and Stock (2023 reprint) ISBN: 978-1666750720 Available on Amazon, Google Books, and through the Penn Museum This edition includes Kramer’s interpretive notes and historical context, which differ from the more literal ETCSL rendering. If you’re comparing translations or analyzing theological motifs, Kramer’s version is especially valuable for its narrative framing and cultural insights.

- British Museum Tablet: Assyrian Confusion of Tongues

BM 85042 (Catalogued tower fragment)

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1882-0711-4883

Anthropological and Cultural Parallels

- Frazer, J.G. The Golden Bough — Global myths of language confusion

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3623 - Oxford Companion to World Mythology – This resource includes thematic entries on mythological structures like towers, ziggurats, and cosmic mountains across traditions (e.g., Mesopotamian, Hindu, Norse).

- Encyclopedia.com’s entry on the Tower of Babel – Offers a detailed historical and theological analysis, including architectural parallels and cultural interpretations.

- Mythopedia – A modern, visually rich encyclopedia of global mythology. While not academic in the strictest sense, it’s excellent for comparative motifs and symbolism.

- Smithsonian Magazine: “Tower of Babel Stele discovered”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-tower-of-babel-stele-that-may-confirm-the-biblical-account-180964894/